It sounds like something out of a fairytale.. a beautiful, remote land, with an enlightened king adored by his subjects.. a place with tall mountains, lush forests, flowing rivers and clean air.. where happiness is valued above all else.

We’re describing the tiny kingdom of Bhutan, wedged between China and India in the Himalayan Mountains. A place so fiercely protective of its unique Buddhist culture that for a long time it sealed itself off… didn’t admit tourists until the 1970s and didn’t introduce television until 1999. A place that charted its own path to development when its king coined the phrase “Gross National Happiness” and made maximizing it the nation’s top priority.

But when a fairytale kingdom meets the modern world, a storybook ending is far from certain.

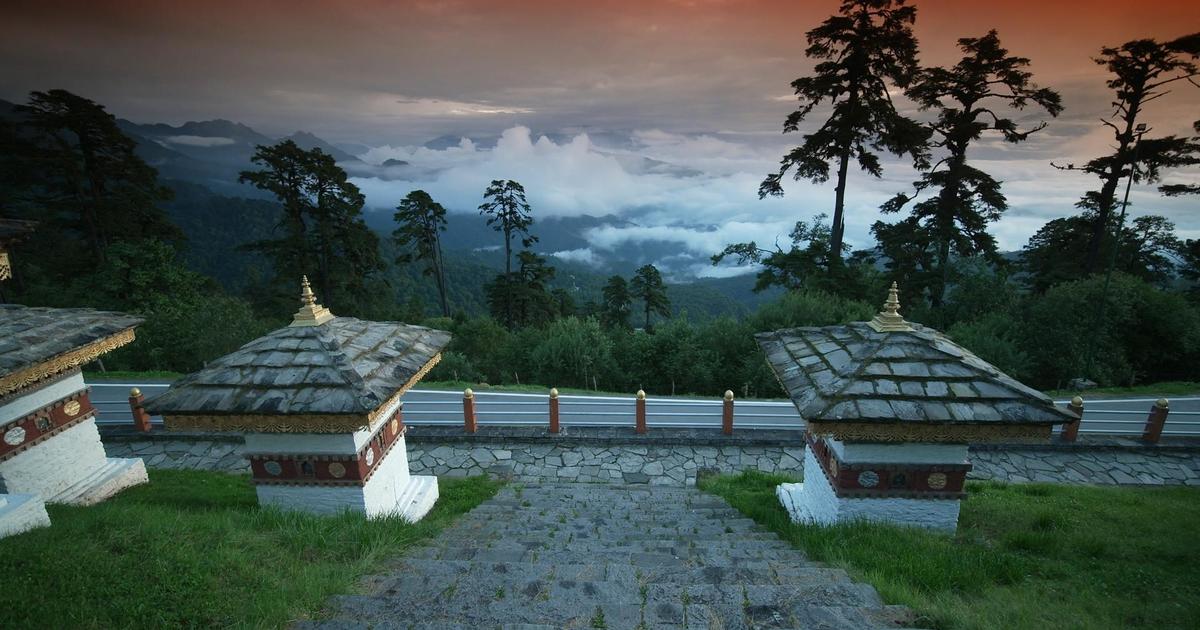

Sunrise over Bhutan’s Dochula Pass.. a place so calm.. so transcendent.. you feel you’ve landed in another time.

Buddhism is the national religion here. We found Bhutanese, especially older men and women, spending hours spinning prayer wheels full of Buddhist scriptures… and prayer flags fluttering on hillsides and in forests, turning nature itself into a shrine. Bhutan’s capital city, Thimphu, still has no traffic lights. The old and the new mingle in peaceful coexistence here, even on the nation’s roads.

60 Minutes

Dasho Kinley Dorji: Bhutan’s story, in one word, is survival.

Dasho Kinley Dorji ran Bhutan’s first newspaper, then served as a government minister.

Dasho Kinley Dorji: We were and still are a very nervous population, between India and China. In the old days, what Bhutan did was we hid in the mountains.

Lesley Stahl: You hid from these two giants–

Dasho Kinley Dorji: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: You were afraid they’d–

Dasho Kinley Dorji: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: –gobble-you-up?

Dasho Kinley Dorji: Oh, yes, yes. Because we don’t have military might or economic force. So Bhutan’s strength was going to be our identity: To be different from everyone around us. We wear different clothes, you know, we construct our buildings in our traditional architecture, an identity based on our culture, that was our strength.

And that culture remains strong.. thousands of Bhutanese gather for seasonal religious festivals, with songs in the national language, Dzongkha, and centuries-old dances and costumes. This is not a tourist-focused spectacle.. though foreigners are welcome. This is clearly for the Bhutanese, who come dressed in their finest.

Lesley Stahl: Tell us about what you are wearing. Because this is the traditional dress for a man.

Dasho Kinley Dorji: My wife joked and said, “It’s the men who wear the skirts in this country,” (laugh) showing our knees. This is called a “gho.” And it’s colorful because it’s all woven here using natural dye.

Lesley Stahl: Very old-fashioned.

Dasho Kinley Dorji: We came to realize that, you know, that what we had in the past, what is old, is actually very valuable.

60 Minutes

Ghos also double as athletic wear for Bhutan’s national sport — archery. They’re using traditional bows and arrows made of bamboo.. shooting at a target a football field and a half away.

Rabsel Dorji: Oh, he’s just hit. He’s just hit. (clapping) So what you’re gonna see is the two teams dancing now. (singing)

Lesley Stahl: They dance?

Rabsel Dorji: And they dance and they sing.

Rabsel Dorji, who once worked at the UN, was a teenager when television came to Bhutan 25 years ago.

Rabsel Dorji: I remember fixing the antenna at my house for my mom to watch. [chuckles]

Lesley Stahl: I wonder how rapidly change has come here. It– it’s almost head spinning.

Rabsel Dorji: My father, my late father, when he was growing up in the ’60s and ’70s, Bhutan was– there was no roads in the country. He had to travel for two, three days on horseback to get to school.

Bhutan was, and is today, largely a subsistence agricultural society, where many families still live in multigenerational farmhouses. The country was unified by the man who became its first king in 1907. His sons and grandsons, who Bhutanese refer to as the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and today 5th kings, have reigned since. But it was the 4th king who as a young, newly-crowned ruler in the 1970s, really set Bhutan on its unique path to modernity. He was flying home from a summit of non-aligned nations in Cuba, and landed at an airport in India, since Bhutan still didn’t have one.

Dasho Kinley Dorji: Indian journalists met him at the airport, and the first question was, “We are– Bhutan is our closest neighbor. We know nothing about Bhutan: For example, what’s your gross national product?” And the king said, “Actually, in Bhutan, gross national happiness is much more important to us than gross national product.”

Lesley Stahl: It just came out of–

Dasho Kinley Dorji: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: –his mouth–

Dasho Kinley Dorji: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: –like that?

Dasho Kinley Dorji: So– sexy headline.

Lesley Stahl: (chuckle)

Sexy headline.. that got international attention. The UN convened a special meeting in 2012 and adopted a resolution urging others to follow Bhutan’s lead. and in Bhutan, it became the primary responsibility of government – led today by Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay.

60 Minutes

Lesley Stahl: Explain Gross National Happiness. What– what is it?

Tshering Tobgay: In the last 300 years, we’ve been obsessed with growth. Gross National Happiness acknowledges that economic growth is important, but that growth must be sustainable. It must be balanced by the preservation of our unique culture. People matter. Our happiness, our well-being matters. Everything should serve that.

So every five years, surveyors travel throughout Bhutan measuring the nation’s happiness. They ask about education level, salary, material possessions.. Do you have negative thoughts? Positive thoughts? How much time do you spend working? Praying? Sleeping? The results are analyzed and factored into public policy.

Lesley Stahl: But people here don’t walk around smiling and laughing all the time. They look to me li– like people everywhere. (laugh)

Tshering Tobgay: Gross National Happiness does not directly equate to happiness in the moment. One happiness is fleeting, it is emotion, it is joy. The other is contentment, to be happy with life, to be happy with oneself. And that’s what Gross National Happiness is all about.

It’s also about nature. By law at least 60% of the country must remain under forest cover, and with most of its energy coming from hydroelectric power, Bhutan was the first and today one of the only countries in the world to be carbon negative. It earns foreign revenue selling excess hydropower to India — and from tourism.. but there are limits.

Lesley Stahl: You have all these gorgeous mountains, but you don’t allow mountain-climbing?

Dasho Kinley Dorji: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: That really surprised me: Why not?

Dasho Kinley Dorji: For a Bhutanese, it’s very easy to understand: You know, the mountains are sacred.

Lesley Stahl: The mountains are sacred?

Dasho Kinley Dorji: Sacred, home of deities. You don’t climb all over it– because it’s sacred. Nature is not something to be “conquered.” You know, it’s something to be respected.

Little boy making presentation: Recycling, separating non-degradable and degradable waste

School is taught in English, and it’s free, as is health care — major accomplishments in a country still considered a developing nation. Oh, and there’s one more thing.. that king who introduced Gross National Happiness… 25 years later decided that happiness required another big change — the right to elect a parliament and prime minister.

60 Minutes

Tshering Tobgay: Bhutan is the only country where democracy was introduced in a time of peace and stability, where democracy was literally gifted, imposed on the people, not just gifted, because the people didn’t want it.

Lesley Stahl: No one was clamoring for it. It wasn’t the–

Dasho Kinley Dorji: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: –French Revolution– there was no revolution. He just decided.

Dasho Kinley Dorji: I traveled with the king—

As a reporter, Kinley Dorji covered the king’s travels to villages all over Bhutan.

Dasho Kinley Dorji: It was called “consultations.” And the only consultation I saw was people begging him not to do this–

Lesley Stahl: Hunh.

Dasho Kinley Dorji: –you know? And that’s–

Lesley Stahl: And so people did not want democracy?

Dasho Kinley Dorji: Yes. Yes. And they’re pleading, and very–

Lesley Stahl: Oh, wow.

Dasho Kinley Dorji: –very articulate arguments on why, because when they looked around the world, their horizon was India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Pakistan: Democracy.

Lesley Stahl: Well–

Dasho Kinley Dorji: Which is really synonymous with– violence, with corruption. So they said, “No, thank you. We– we didn’t really– we (laugh) don’t really need that. We are fine.”

Lesley Stahl: He defied the people and imposed democracy.

Dasho Kinley Dorji: But he– you couldn’t argue with him. He had arguments like, “You leave this small country in the hands of one man, who’s chosen by birth and not by merit. Small country’s finished. One day, we’ll have a bad king.

And with that, the 4th king abdicated at just 51, passing the crown to his 26-year-old son, the 5th and current king. Bhutanese headed to the polls for the first time ever. The result is hard to wrap a Western head around.. a democracy where the king is universally adored — that’s him swearing in the prime minister — and the two work together as partners. Quite the happily ever after ending… except this would-be fairytale has an unexpected plot twist..young Bhutanese are leaving the country in record numbers.

60 Minutes

Tshering Tobgay: This is a very difficult situation for Bhutan.

Lesley Stahl: You called it existential.

Tshering Tobgay: It is an existential crisis.

So how did Bhutan, a country that prioritizes its people’s happiness, find itself with so many of them leaving? Well it started with COVID, which hit Bhutan’s economy hard, shutting down tourism, and recovery has been slow. Many Bhutanese — with their excellent English – found higher-paying jobs in Australia, even doing menial labor. Word spread on social media, and now a devastating 9% of the country’s population has left.. most of them young.

Bhutan’s government has mobilized, with the king launching a bold, high-stakes plan, and something of an experiment.. can he create a place where development — and wealth — can coexist with sacred values?

Namgay Zam: It’s a lot of people with skills who are leaving, right, people in my age group.

Namgay Zam is a journalist, who used to anchor Bhutan’s nightly newscast.

Namgay Zam: All of my friends who are journalists, they are all outside. There are just two of us left in the country. Editors, graphic designers– sound people. Yes, Lesley. Yes.

Lesley Stahl: They’ve left the country?

Namgay Zam: They’ve left the country.

Outside Bhutan’s airport, we saw what looked like a sort of picnic, but was actually a goodbye.

Rabsel Dorji: The whole family tends to go to the airport.

Often, Rabsel Dorji told us, several generations.

Rabsel Dorji: We’re very close to our families. And so when someone leaves so far away, they don’t know when the next meal together in the family will be.

— plane on runway, pans to family waving above —

Rabsel Dorji: There’s another vantage point where you can see the plane take off. And so many of the family members will wave them goodbye and see them off. That’s a very emotional experience.

60 Minutes

Lesley Stahl: So many of your people are leaving– I– I have to ask you this, has Gross National Happiness been a failure?

Tshering Tobgay: Gross National Happiness has succeeded.

Lesley Stahl: But if people are leaving.

Tshering Tobgay: I’m 58 years old, in my generation Bhutan has transformed from a Medieval society, literally with no roads, no clean drinking water, life expectancy in the 40s, very few schools– to what you see today We have free education, free healthcare, where life expectancy is now crossing 70 years old. Where our economy, while it is still small, has been growing in the last 30 years. It’s been growing on average of– of about 6%, and it’s growing without destroying, undermining our culture. So by these measurements, I would say Gross National Happiness has succeeded. As a matter of fact, perhaps it has succeeded beyond our wildest dreams.

Meaning he believes it’s ironically the success of Gross National Happiness that has made bhutanese young people sought after abroad.

Tshering Tobgay: We have to lure them back, and the only way to lure them back is by good, well-paying jobs.

So he’s trying to attract more business and tourists to Bhutan, highlighting landmarks like this centuries-old suspension bridge, part of an ancient 250-mile trail from one end of the country to the other..now restored to welcome trekking tourists.

And near the bridge, at twilight, one of the most beautiful buildings we’d ever seen, built in the 1600s. But tourism can only do so much, and Bhutan’s king knows it. So while he never gives on-camera interviews..he did grant us a royal audience to share what might be called an enlightened hail mary. He’s decided to create a new city in southern Bhutan with different rules from the rest of the country.. an attempt at a new model of robust economic development, still true to Bhutanese values. He’s calling it the Gelephu Mindfulness City. And to design it, he turned to Danish architect Bjarke Ingles.

Bjarke Ingels: There’s a real reason why you do something out of the ordinary.

Ingels is known for his innovative buildings, like this New York City skyscraper.

Lesley Stahl: What’s the biggest challenge here?

60 Minutes

Bjarke Ingels: The big question is, can you create a space for economic activity and the future without sacrificing the values and cultural riches that they have today?

Bjarke Ingels: You have 34 rivers.

As Ingels showed us in these renderings, the new city will have neighborhoods nested between the area’s many rivers, connected by a series of unusual bridges.

Bjarke Ingels: We got the idea that the bridges could be like the public buildings.

Lesley Stahl: This is a bridge?

Bjarke Ingels: This is a bridge that is also a kind of Buddhist center.

Lesley Stahl: Oh,

Bjarke Ingels: This is a health care bridge. It actually has, health care facilities, on either side of the road. This is a university bridge.

All built with local materials. This will be the downtown. No skyscrapers.

To see the site, we flew about an hour south of the capitol, leaving behind those sacred Himalayan peaks, for Bhutan’s tropical lowlands, and we climbed to a lookout, where there wasn’t much to see..

Lesley Stahl: This is empty right now. You’re going to have a whole new city here.

Dr. Lotay Tshering: We are looking at a small piece of the city.

Our guide was Dr. Lotay Tshering, a former prime minister who the king has tapped to govern the new city. He told us it will be built in phases over the next two decades, with no polluting industries allowed.

Dr. Lotay Tshering: We have lots of wildlife. Very, very rich wildlife. The most prevalent are the elephants.

Lesley Stahl: You have elephants?

Dr. Lotay Tshering: Yes.

60 Minutes

And sure enough, we spotted this family a few hours later, just off the side of the road. As habitat shrinks elsewhere, more elephants and even tigers are finding a safe haven in Bhutan, and the new city will have wildlife corridors to protect them.

Lesley Stahl: The king has said, “The future of Bhutan hangs on this project.” It’s huge.

Dr. Lotay Tshering: Doing the way we had been doing is not enough anymore. Bhutanese when we say we follow the principles of Gross National Happiness, we do not mean we are happy with less. That’s what I feel. We are human beings. We also want more. We also want to be rich. We also want to be technologically high standard. We want Bhutanese to be heading– multi-million dollar companies, multinational companies. But following a philosophy of Gross National Happiness.

How’s that supposed to work? Well, this Bhutanese team is collaborating with experts around the world, seeking investors for what’s sure to cost in the billions. The city will have its own legal framework modeled on Singapore’s, and will offer plentiful, clean hydroelectric power they hope will draw technology companies, especially AI.

Bjarke Ingels: So imagine this is the upper part of the river..

To capture that hydroelectric power..

Bjarke Ingels: This is roughly 500 feet.

Ingels has designed a colorful dam.. that’s also something you can walk down.

Bjarke Ingels: All of these little diamond shapes are actually stairs. And you get this, this experience. So here you’re standing at the top of the dam looking down. And then you can see, like, this major roof is the temple

Lesley Stahl: A temple?

Bjarke Ingels: A temple–

Lesley Stahl: On–

Bjarke Ingels: On the face of the dam, overlooking the river and the valley.

Lesley Stahl: I bet the king loves this.

Ingels presented his plans to the king.. and the king to the nation.. last December.

Bjarke Ingels: On December 17, the National Day of Bhutan, they fill a stadium, a sports stadium. So when you go to that stadium–

Bjarke Ingels: It looks like a Quidditch match–

Lesley Stahl: [laugh]

Bjarke Ingels: And the king basically speaks to his people.

His topic: the Gelephu Mindfulness City and his hopes for the opportunities it will create to keep Bhutanese in Bhutan. Namgay Zam, meanwhile, had different plans.. involving Australia.

Lesley Stahl: You thought about leaving.

Namgay Zam: Oh, I didn’t just think about leaving. Like, everything was underway.

But then she went to hear the king that day.

60 Minutes

Namgay Zam: And he did what no king had done before. He asked the people to help him directly. And he said, “Will you help me?” And there was shocked silence. Even for me, I froze. And I was like, “Did he just ask us to help him?” And then he said, “Will you help me,” a second time.

Namgay Zam: And there was a resounding, “Yes.” And I said, “Yes.” And then I came home and I told my husband, I said, “We can’t leave.” And he said, “Why?” And I said, “I’ve signed a social contract with his majesty, because I said, ‘Yes.’

Lesley Stahl: You’re so sophisticated. You’re worldly. And yet, your king asked you to help. You were leaving.

Namgay Zam: And I wasn’t the only one. There was, like, 30,000 people there. (laugh) And I felt like he asked me.

She’s decided to stay. And instead, it was the king and his family who went to Australia just last month.. to bring his vision to 20,000 Bhutanese who live here now and who he’s hoping to one day lure back home.

Bjarke Ingels: If we succeed, we can show that you can create a city that does not displace nature, that is anchored and rooted in the local heritage and culture, and that still allows for prosperity and growth to happen. That is a challenge that a lot of places in the world are struggling with.

Culture.. tradition.. modernity.. if this remote fairytale land can gracefully master that dance, then perhaps they’ll have something to offer the rest of us.

Produced by Shari Finkelstein. Associate producer, Collette Richards. Broadcast associate, Aria Een. Edited by Sean Kelly.

Leave a Reply