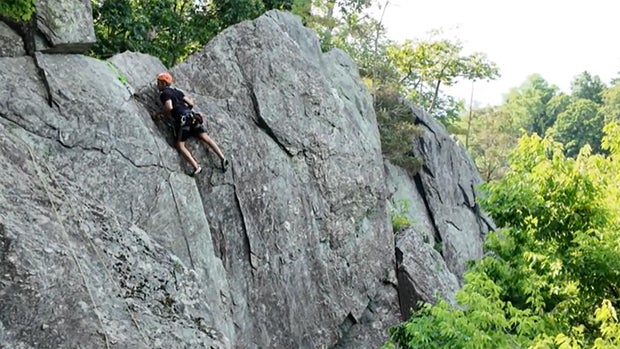

We were amazed at what we were seeing on a sweltering summer’s day, when a group of people with Parkinson’s Disease began rock-climbing on the Carderock Cliffs of Maryland. Yes, rock-climbing!

It’s all part of their therapy, says Molly Cupka, the no-nonsense instructor and cheerleader for this community of courageous climbers.

CBS News

She started this program, called UpENDing Parkinsons, as a non-profit twelve years ago.

“There’s a lot of balance involved, mobility involved, strength, cardio, and then there’s the cognitive part, where you have to look at the hold, and figure out how to get your body to move to get to that hold,” she said.

How often do they fall? “Falling is definitely part of climbing,” said Cupka. But they never really fall, because they wear a harness that provides a layer of safety. “You’re always on the rope. You fall, but you don’t fall far. We always say if you’re not falling, you’re not trying hard enough!”

There’s no cure for Parkinson’s, which usually affects mobility, coordination, balance, and even speech. Jon Lessin was diagnosed in 2003. He was once an all-around athlete. About 12 years ago he retired as a cardiac anesthesiologist because of Parkinson’s. His daughter, Brittany, watched his steady decline, until he discovered climbing walls as high as 60 feet!

“My dad has a hard time walking across the room, but he can make it to the top of this giant wall,” Brittany said. “There’s a lot that he’s had to give up because of his disease. But this is something that he found through it, which is really cool.”

CBS News

Jon said, “I get to the top and I feel like I’ve conquered something. And I feel like the wall can’t beat me. I can beat the wall.”

Full disclosure: This story is very personal to me. My late husband, Aaron Latham, had Parkinson’s, and boxed as a way to fight the symptoms, as he explained on “Sunday Morning” in 2015. “Boxing’s just the opposite of Parkinson’s,” said Latham. “Everything’s designed, instead of to shrink you, everything’s designed to pump you up.”

Jon Lessin said Parkinson’s “makes you feel very small. You make small movements, you’re hunched over. And [rock climbing] makes you feel like you can accomplish the world.”

It was Lessin who first had that big idea to use rock climbing as a therapy for Parkinson’s. “I wanted to do big-movement exercise,” he said. “And I found Molly at this gym.”

Lessin proposed the idea to Molly Cupka, who runs the Sportrock Climbing Center in Alexandria, Virginia. She thought it was worth a try, given the sport requires participants to plan ahead, to know where to position their hands and feet. “I wish I could go into the brain and see what’s happening while people climb,” Cupka said.

Some people with Parkinson’s, like Vivek Puri, get dyskinesia (involuntary jerking motions). Puri said he’s usually unaware of his. He runs a home building company in the D.C. area, and was only 38 when he found out he had Parkinson’s. “Fine motor skills have kind of really suffered dramatically,” he said. “When I don’t climb for some periods of time, I get worse.”

But once he gets on the wall, he calls himself Spider-Man.

CBS News

“Honestly, I climb like a monkey,” he said. “I get my finger strength moving, which gets my fine motor skills – maybe not back, but kind of keeps that in motion.”

There’s no evidence climbing slows the progress of Parkinson’s, but Cupka joined forces with Marymount University last year to study patients climbing for the first time. “We have people literally walking and carrying weights, you know, walking and looking, multitasking,” she said.

The study found that, in so many words, if you climb, you may walk better.

Mark de Mulder, a musician and former director of the National Geospatial Program, doesn’t need a study to prove what climbing does for him. “It allows me to say, ‘All right, take that, Parkinson’s! I’m doing this!’ It just makes me feel stronger, and I’m fighting it. I’m doing something about it.”

CBS News

Many of the climbers have become friends who climb together several times a week; and they’ve become a support group, Parkinson’s Pals, who encourage each other.

“When I reach the top, I can turn around and look and wave, and see my wife and my friends, and that’s the reward,” said de Mulder. “It’s really wonderful.”

There’s no real understanding of how these people can do this, but you can certainly understand why. An emotional Vivek Puri said, “It’s nice to be good at something.”

CBS News

For more info:

Story produced by Richard Buddenhagen and Kay Lim. Editor: George Pozderec.

See also:

Leave a Reply